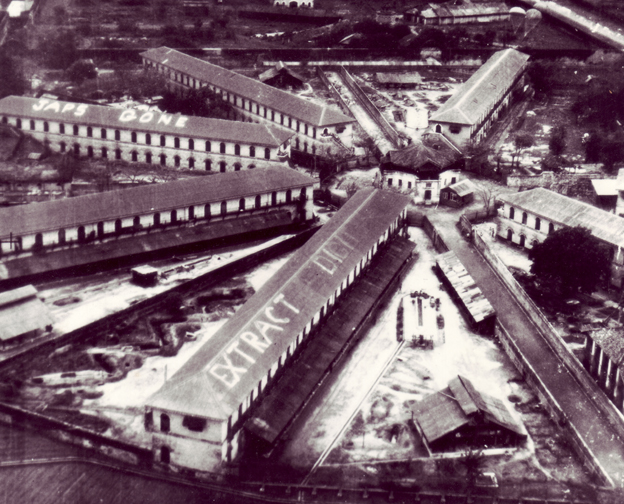

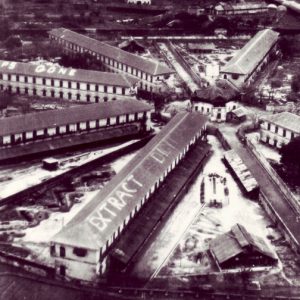

“Extract Digit.” In an iconic photo, these two words are painted in whitewash atop a building in a Japanese prison compound in Burma. A day earlier, the guards had abandoned the camp and the prisoners painted “Japs Gone” atop another of the buildings. When British fighter planes passed overhead, the pilots took the message for a ruse and strafed the camp. So the British POWs climbed atop another building and wrote “Extract Digit.” The next day, when the fighter planes flew overhead, they not only didn’t strafe but returned and dropped supplies into the camp. The pilots knew the Japanese likely wouldn’t have thought to write such a phrase, which, loosely translated from the British, means “Take your finger out of your ass.”

Karnig Thomasian, one of the 19 ex-POWs interviewed in “Prisoners of War: An Oral History,” was a prisoner in the compound, where he endured regular beatings and starvation. Tim Dyas, a sergeant in the 82nd Airborne Division, parachuted with his squad into Sicily, landing in the midst of the Hermann Goering Panzer Division. After a firefight that broke out in the middle of the night and lasted into mid-morning, he found himself facing two German tanks, and had to make a life or death decision which would affect not only him but the ten remaining men in his squad. “Surrender,” he said. “Intellectually it was the right thing to do,” he said many years later. “Emotionally I’ve never gotten over it.”

Mary Previte was the daughter of Christian missionaries in China when the Japanese took over her school and moved the children and staff to the Weihsien concentration camp. For the next three years the teachers and school administrators made sure the children had structure in their lives and continued with their lessons. As the war neared an end, the Allies feared the Japanese might execute some or all of the 100,000 prisoners spread throughout China, so one day a B-24 flew over the camp and a half-dozen men parachuted into a field outside the camp. Fortunately the guards had abandoned the camp and there was no violence. But for 12 year old Mary Taylor, these six liberators who came down from the sky were her heroes. For the next few weeks she followed them around like a puppy, and she took all six of their names. Later in life, Mary became a state assemblywoman in New Jersey. One day a colleague asked her to deliver a proclamation to the local chapter of the China Burma India veterans association. After reading the proclamation, Mary told a little of her story, and then she read the names of her six heroes and asked if any of them were in the audience. None were, but a gentleman in the rear spoke up and suggested that she send the names to the association’s newsletter. This began a journey of hundreds of phone calls and letters and research, and within two years she had met two widows and four surviving members of the group that liberated the Weihsien concentration camp.

These and 16 other ex-prisoners of war share their unique yet interrelated stories in “Prisoners of War: An Oral History.”

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.