This page is still under construction

(and so am I)

When I finally graduated from the City College of New York, after five and a half years, I took a year off and went to live in Europe. I spent eight months in Paris, where I would sit in outdoor cafes on the Champs Elysees and dream of writing the Great American novel. Passers by would see me scribbling in a notebook and say something like “Alors, vous etes le nouveau ‘Emingway?” Loosely translated: Are you going to be the next ‘Emingway? I would smile back and think “I wish.” If somebody had said “Alors, vous etes le nouveau Studs Terkel?” I wouldn’t have known who they were talking about. The year was 1971.

Fast forward 52 years and here I am, waiting for someone to call me the next Studs Terkel.

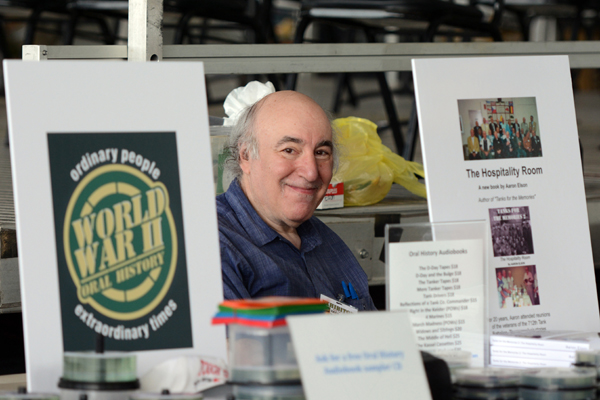

When I began interviewing World War 2 veterans, at a reunion of my father’s tank battalion, I would say what I was doing was like oral history. One day a friend said it wasn’t like oral history. It was oral history.

Since I began comparing my work to that of Studs Terkel, probably the best-known oral historian, I thought I should learn more about him, so I visited the “Fresh Air” archives at the National Public Radio web site — I always get a kick out of the way Terry Gross pronounces “Fresh Air” by sending a gust of wind through the word “Fresh” so it comes out with a whoosh, but I digress. I listened to a pair of interviews Terry did with Studs Terkel and one remark stuck with me. He spoke about the famous scene in “Five Easy Pieces” in which Jack Nicholson harasses a waitress because the diner won’t allow substitutions. The scene is celebrated for Nicholson’s clever approach to ordering a side of wheat toast when no side orders are allowed, by ordering a chicken salad sandwich on wheat toast, and telling her to “hold the chicken.” Terkel said that nobody thinks about the scene from the waitress’s point of view. Was she having a bad day? Did the film give a damn about how she was affected?

I thought about that. The waitress was ordinary people, the kind Studs Terkel celebrated in his work. Those are the kind of veterans I’ve celebrated in my work, the mechanics, the loaders, the privates and Pfc’s, the sergeants and drivers and gunners who rate at best a few paragraphs in the sweeping narratives of World War 2.

I conducted my first interview in 1987 at the 712th Tank Battalion reunion in Niagara Falls, New York. I went to the reunion hoping to find veterans who remembered my father, who passed away seven years before. I met Jule Braatz, the sergeant my father reported to in Normandy as the replacement for the first officer in the battalion to be killed.

Braatz was the only veteran I interviewed that year. I missed the 1988 reunion but went in 1989 and never missed another reunion.

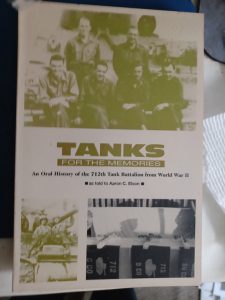

By 1993 I had a pile of transcripts that I thought might be the basis for a great book. Goodbye Mr. ‘Emingway, hello Mr. Terkel. Having never served in the military myself, I felt it important to present the stories in the veterans’ own words. Unable to find a publisher or even a literary agent, I decided to publish the original “Tanks for the Memories” myself.

But I didn’t stop there. I expanded the chapter on Hill 122 into a separate book, “They Were All Young Kids,” and followed that with “A Mile in Their Shoes: Conversations With Veterans of World War 2.”

Still I was getting nowhere with agents or publishers, but I got a nibble from a big agent who said he loved oral history. He said one of his favorite books was “The Glory of Their Times,” about the early days of baseball. So I ran out and bought a copy, loved it, and modeled my next book, “9 Lives: An Oral History” after that, presenting narratives drawn from nine of my interviews. The agent passed, so I published it myself.

When the original Tanks for the Memories came out, the Internet was still young and I thought I needed a presence to promote the book. I bought space on a military history web site with a “url” so long I could barely remember it myself, but I was like “Hey everybody, I have a web site.”

I purchased my first domain in 1997, called the web site World War 2 Oral History, and began posting stories from my interviews. The site took on a life of its own. Documentarians contacted me and asked if they could use material from the site, or if I could suggest veterans for them to interview (three of them were interviewed for Patton 360). Russians spammed my guest book. Authors used material from the site and mentioned me in the end notes. The site showed up on the first page of several now-defunct search engines such as Mamma, Altavista and Excite.

As veterans of the 712th Tank Battalion retired to or spent winters in Florida, they organized an annual “mini-reunion” in Bradenton, where one of their members was the mayor. I would drive down from New Jersey and would listen to cassettes of my interviews on the 16 hour trip each way. I thought that these would make great books on tape. I dropped the idea after two time-consuming attempts to dub and splice and measure two such audiobooks. But then along came writable CDs and affordable sound editing software, and I was off to the races. I created a series of oral history audiobooks, which were quite popular with history teachers and truck drivers, as an hourlong CD could eat up 80 miles of highway. But vehicles no longer have CD players, so I’m transitioning to audio on flash drives. Stay tuned!

As I approached the age the veterans were when I began interviewing them, I began looking for ways to make their stories relevant to younger generations. It seemed like a podcast was a good idea. So I launched the War As My Father’s Tank Battalion podcast. More than 100 episodes are available at Spotify and iTunes or wherever you like to listen to podcasts, and while new episodes are on hiatus the podcast will be resuming soon.

Recently my three main websites crashed and I had not backed them up properly. My website host said they were infected with malware, although I suspect it had to do with the host company merging with another host company. I had spent a good deal of money and hundreds of hours building them with the help of a subscription tech support company. I decided to delete all three web sites, losing a great deal of content, and to begin rebuilding them myself, hoping I learned enough from the tech support service so that I would not need expensive help. How’m I doing?

A literary agent once told me that the target market for my books was dying at a rate of a thousand a day. The World War 2 veterans were not my target market, their children and grandchildren and nephews and future generations were, but this agent seemed too shortsighted to recognize this. In keeping with my motto, “Where the latest generation meets the Greatest Generation,” I’ve begun experimenting with TikTok, Instagram and Facebook Reels; and while nearly all of my interviews were on audiotape and later digital voice recorder and I never videotaped my interviews, I’ve opened a YouTube channel as well.

I hope you’ll revisit this site from time to time, as the rebuilding process is ongoing and there will frequently be new material.

–Aaron Elson