Tiger Burning

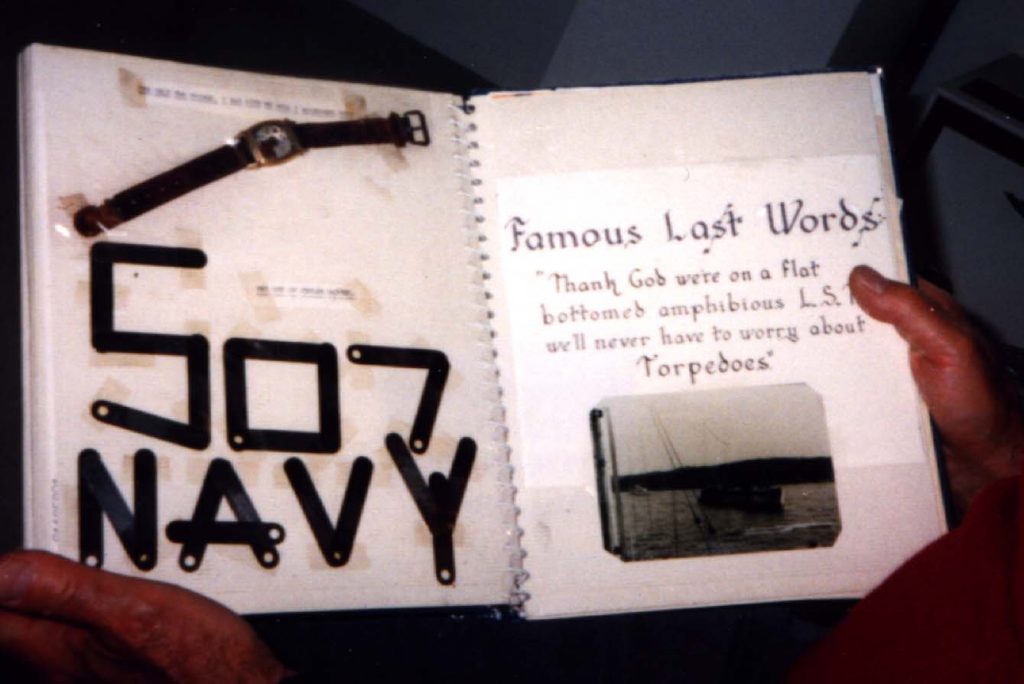

Angelo Crapanzano has a set of feeler gauges — narrow, thin strips of gunmetal gray steel with various markings — in his memorabilia book. They are arranged to spell “US Navy LST 507.” The feeler gauges and the smashed, faceless remains of a watch he was wearing on the night of April 28, 1944, are there to remind him of the ship he loved — the Large Slow Target — LST actually stands for landing ship, tanks — that was intended to carry tanks and troops to Utah Beach but instead was torpedoed by German E-boats in a training exercise gone awry.

I first learned of Exercise Tiger while interviewing D-Day veterans for the Bergen Record. Lou Putnoky, a Coast Guard veteran who was on the USS Bayfield, suggested I read a book called “Exercise Tiger,” by Nigel Lewis. I found the book in the Hackensack library. While I was reading it, the Record ran a wire service story on the 50th anniversary of Exercise Tiger. I wondered if I might not be able to find a survivor of the operation who lived in our readership area.

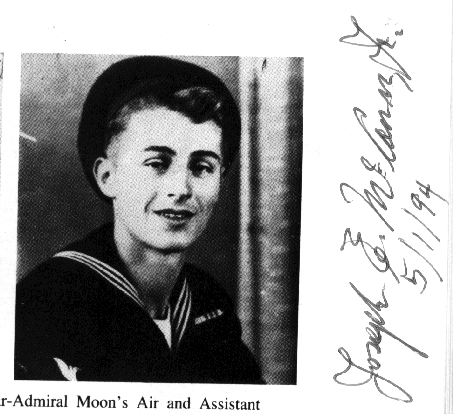

The next day, I came upon a passage that mentioned Angelo Crapanzano of New Jersey. This was in the days before I discovered the Internet, but the Hudson County phone book yielded an A. Crapanzano in West New York. When I called him, he had just returned from a ceremony in New Bedford, Mass., at which he was reunited for the first time with John McGarigal, whose life he saved fifty years earlier, and Joe McCann, who rescued them both.

“Tiger Burning” is the title of an unpublished book written by Dr. Ralph C. Greene, who was instrumental in bringing many of the details of Exercise Tiger to light. E-boats were long, sleek surface vessels that prowled the English Channel at night hunting for prey.

Angelo Crapanzano

There were something like 20,000 guys involved in Exercise Tiger. They started in January having these dress rehearsals for D-Day. There were three before us, one was Beaver, I forget the other names.

One of the reasons that the first three exercises had no problems was because when they had them, the English Channel was pretty rough. Rough water’s not good for E-boats. They want calm water. So what happens, when it’s time for Tiger, the water was like a lake.

The English Channel can be like a lake, and also it can be rougher and nastier than the Atlantic Ocean when it whips up. You can go from one extreme to the other. A lot of people don’t realize how rough the English Channel can get.

There were eight LSTs. The first five came out of another port, and they went out into the Channel and waited. Now around dusk, the other three LSTs — the 507 that I was on, the 531, and I’m not sure about the third — when it came time for us to go out and rendezvous with them, we had two British corvettes to escort us. When we got out there and lined up, the corvettes turned around and went back to England. A lot of us were wondering why these ships were going back, where the hell is our escort?

We ended up with one escort ship. It was about a mile in front of the lead ship, so the sides are wide open. My ship, the 507, is the last ship in line, which is uh-uh, bad. That’s how they hit them. But nobody ever even suspected that a thing like this would happen. The element of surprise was devastating. Plus, what made it bad is that it was 2 o’clock in the morning, and it was dark.

The day before this operation, I received a tetanus booster shot. The last time I’d had a tetanus shot was in boot camp, and I ended up with a 104 fever. So they gave me this booster shot, and the next day, as we’re approaching this convoy, I started to feel funny, and I thought, “Don’t tell me I’m gonna get sick again.”

I was concerned, because I had the midnight to 4 in the morning watch in the main engine room. It was approaching midnight, so I went down in the engine room. My engineering officer was down there, and I told him — well, I didn’t tell him, you can’t actually talk, when you’ve got two big 12-cylinder diesel engines running full speed they scream, you have to wear cotton in your ears, and you have to either read lips or motion. I told him, “I don’t feel good, I feel like I’ve got a fever.” So he said, “Go up to the pharmacist’s mate.”

I go up to the pharmacist’s mate, and he takes my temperature, sure enough, 104. So he says, “What are you doing out of your bunk?”

I said, “I’ve got the 12 to 4 watch.”

“No,” he said. “Go down and tell the engine room officer I told you that you should go to your bunk.”

I go back down to the engine room and I tell him, so he says, “All right, I’ll cover you.” So I go up to the crew’s quarters — and I got this weird feeling that where the hell is my Mae West, my life jacket? And I start looking for it. There are life jackets all over the place, on top of the lockers, under the lockers, and I’m looking, I’m looking, and I find it. It’s all full of dust. My name, “Crappy,” was on it, because everybody called me Crappy. They’ve been calling me Crappy since grammar school, for Chrissake. So I grab my life jacket, I take it over to my bunk, and I lay it right on my bunk. And I lay down. I must have gone to sleep. I don’t know how long I was sleeping, but all of a sudden, general quarters was sounded. So I jumped up, and without even hesitating I grabbed my life jacket and started running for the engine room, and I’m lacing it up, and as I’m going down the ladder I hear 40-millimeter guns going boom-boom-boom.

My job in general quarters was up in the front of the engine room where they have the enunciators for the wheelhouse. When they change the speeds, it was my job to note the change and record it in a log. That log is very important in the Navy, in case two ships have an accident, the first thing they want to see is the log and the speeds. And I’m getting all these changes of speed, and thinking, “What the hell’s going on?” Full speed, half-speed, stop. Quarter speed. I’m writing all these things, and the last thing I remember writing is 2:03, I know exactly when it happened.

Everything went black. There was this terrific roar, and I got this sensation of flying up, back, and when I came down I must have bumped my head and must have been out for a few seconds. When I came to, I felt cold on my legs. And it was pitch black.

I knew the engine room like the palm of my hand. I knew I had to go forward and to either corner, and there was an escape ladder on either side. I ran to the ladder and I went up. When I got topside, I couldn’t believe what I saw: The ship was split in half and burning, fire went from the bow all the way back to the wheelhouse. The only thing that wasn’t burning was the stern. And the water all around the ship was burning, because the fuel tanks ruptured, and the oil went into the water. On the tank deck we had fifteen Army ducks [DUKWs], and every Army duck had cans of gasoline on them, and all that was going into the water, so it was like an inferno.

And then the soldiers were panicking. You couldn’t blame them because they’re not trained for disasters at sea. They’re trained for land, for fighting. A lot of them were jumping over the side immediately without even waiting for the captain to say abandon ship. The ship was crowded with personnel, because every LST had two or three hundred Army personnel with all the vehicles, this was a real dress rehearsal. They had to do that for the guys to get used to the ships, where the heads were, how to go to eat. Also, how to dog down their equipment so it doesn’t roll and slip. It was so crowded that a lot of the soldiers were sleeping topside on their vehicles. When the torpedo hit, a lot of these guys got blown right into the water. There were even small jeeps that got blown into the water. It was an inferno, and the only place that wasn’t burning was the stern. So I ran back there.

Now there’s a bunch of guys back there, and everybody’s wondering what happened, what the hell’s going on? In the meantime, while we’re standing there, the 531 gets two torpedoes and it goes down in about ten minutes. They claim that maybe ten or twelve guys got off of that ship. It went down fast. Two, I mean two, that’s bad.

Now the captain yells to the gunnery officer, “Empty the magazines of all the 40-millimeter shells!” He was worried that it was gonna get so hot it would blow the whole thing. So we formed a line and they were passing the cans with the shells, and we were throwing them over the side. That lasted about ten minutes. Then he said, “Abandon ship!”

So this is tough, because a thousand things are running through your mind at one time. Oh, wait a minute, while we’re standing there, the gunnery officer says, “Here comes another torpedo!” And we look over, and there’s this thing coming right toward the ass end of the ship. You know what kind of feeling that is? Your blood freezes. Your mind goes blank. Because you’re almost saying to yourself, “What’s this going to feel like when it hits? I’m dead. We’re dead.” It missed us by no more than ten or twelve feet.

Now we’ve got to go into the water, because it’s getting worse. There were a lot of guys on the front end of the ship, and the tank deck was burning right under them. I had guys telling me that they hesitated, a lot of guys didn’t want to jump in the water right away. It got so hot on the deck that their shoes started smoking, because the tank deck was burning fiercely, and that’s all metal. It’s just like a gas jet stove. And all the heat’s going up to the top deck.

All right, so you’ve got to jump. And I run to the railing and I look down and I see all these guys in the water already, now I say, “What am I gonna do? I’m gonna jump and I’m gonna hit somebody.”

Then I’m saying — this is all in a split second — “When I jump in the water somebody’s gonna jump on top of me. When I jump in the water how deep down do I go before I come up? Or do I come up right away?”

In the engine room you had to take readings of a bunch of gauges, like seawater temperature, oil temperature, because the seawater cools the engine. I knew that the reading on the salt water coming in was 43 degrees. The thing I didn’t know is what 43 degrees felt like. So when I hit the water, it took my breath away, that’s how cold it was. It was frigid. It was unbelievable, unbelievable cold.

I must have gone down a good six or eight feet. Because this is a 40-foot jump. You had to climb up over the railing and then jump. But it’s feet first, you get down nice and clean. So I come up. Then I was worried about the flames in the water, but they were further up, the whole back end of the ship was good yet. So we’re all back there, a bunch of soldiers and all the sailors. And also there is this guy, my shipmate, John McGarigal. He was a storekeeper, and he was in the wheelhouse when this happened. I met him over this weekend, and I asked him, because I wondered, I said I knew that all these guys topside had to wear helmets, and then I knew that he had a gash in his forehead and he was bleeding like a stuck pig. And I said to him, “Didn’t you have your helmet on when the torpedo hit?”

He told me he had just removed his helmet because he was sweating, to wipe his brow, and that’s when it hit, so he had no helmet, and the concussion blew him from one side of the wheelhouse to the other and he banged his head.

So we’re all back there in the water, what the hell do we do now? And what the hell is going on? Who hit us? What was it? We didn’t know.

Then we see these large oval life rafts, every LST carries about 12 of them around the outer rim of the ship. In an abandon ship, the chief boatswain’s mate is supposed to go around and cut them loose, and they slide right down into the water. But it didn’t happen that way. Out of the 12 life rafts that we had, they said only two or three got released, and we were lucky, we got one of them. We see this life raft drifting towards us. It had gone through all the flames in the water, and it was all burnt. The whole center was gone. Now these life rafts are big, and very wide, and the outer rim is about a foot around. In the center is a wooden platform, plus they have water, fish hooks, all this crap for survival, that was gone, that was all burned away, and the outer rim was all charred. But it was buoyant and was floating. So when I saw it I said, “Let’s grab this thing,” and it was coming toward us. So I grabbed on, and McGarigal next to me, and nine soldiers got on it, there were eleven in all when we started.

I said, “We’ve got to kick like hell, get the hell away from the ship,” because when it goes down it’s gonna suck us down with it. And also, we’ve got to get through all this water that’s burning. So by kicking a lot and splashing we finally, little by little, got to the outside of the flames. It was a matter of hanging on and surviving, and we drifted away from the ship. I could see my ship burning and little by little going down, even from a distance.

The water was full of bodies. I saw things that I couldn’t believe. I saw bodies that were, what’s the right word, they were stuck all together and charred, they were fused together and all black. They had gone into the fire and never got out.

What killed the majority of the soldiers was the cold water, hypothermia. The other fact was that 95 percent of them had their life jackets on wrong. They had them around their waist instead of under their armpits. A lot of them jumped in with their packs on their backs, with their rifles, I don’t know what the hell they were thinking of, you shouldn’t carry any weight into the water. But it was a complete panic. They wanted to get the hell away from the ship. The water killed more people than the actual torpedo. I saw bodies with arms off, heads off, heads split open, you wouldn’t believe what goes on, it’s unbelievable. A lot of them were literally blown into the water. I understand that some soldiers got out of the tank deck through an opening in the side, the opening couldn’t have been made by the torpedo, but it could have been made by the concussion. I don’t know how many but some of the soldiers got out of the tank deck through this opening and they were burned before they even got into the water, because the tank deck was an inferno.

Here’s another thing, to show you how cold the water was. After I was in the water no more than an hour, I couldn’t feel my legs anymore, it’s like there’s nothing there. Then I was starting to really worry, because I used to read these stories about the Murmansk Run in the North Atlantic, of course the water’s even colder up there, so a ship would get hit and if the guys are in the water any length of time, they used to have gangrene, they’d take their legs off. I didn’t like that, I mean this is what kept going through my mind. I thought, who the hell wants to live with no legs?

I knew about hypothermia. When I started to feel this sensation like my legs were not there, the nine soldiers were still on the raft, and I kept saying to them, “Don’t fall asleep, whatever you do. If you fall asleep you’re dead. Keep kicking your legs. Sing. Talk. Do anything, but don’t fall asleep.” And little by little, they kept kicking, there was conversation, but then after a while it started into a lot of praying and yelling, and I heard it going on all around me, guys screaming.

I started to realize that, hey, we’re gonna be here a long time. Is anybody coming back for us? Then I started to worry about, will these E-boats come around and maybe take us as prisoners of war? All these things go through your mind.

So what happened after a while, after about two hours, three soldiers said, “We’re gonna make a swim for it.”

I said, “You’re crazy. What do you mean, make a swim for it? You don’t even know where you are. You don’t know what direction you’re gonna go. Suppose you go in the wrong direction?”

They went, and that’s it. Those three, gone. And then a little while later, I had an Army lieutenant on my raft who went completely berserk. Yelling and screaming and he lets go, and he’s gone.

Now there’s five soldiers left.

And little by little, time went on and on and on. And in the course of the next period of time, after the lieutenant went, every half hour or three quarters of an hour, one of the other guys would just fall asleep and slip off. Now you’ve got to understand that as time goes on, I’m not feeling so great either. I’m losing a lot of my strength. You lost a lot of your ability to think straight, too. And little by little, all the soldiers went. That was it. They were gone. It was just John and I.

Now it’s got to be close to dawn. It’s still dark. I’m in bad shape, and McGarigal’s been unconscious for two and a half, three hours already because he lost a lot of blood. He had some gash. I was holding myself to the life raft with my left hand and I was holding onto McGarigal with my right hand. And then it got to a point where I must have went in and out of consciousness myself.

You’ve got to know something else that happened to get the idea of what this is all about. For forty years after the war, this was a complete secret. The only guys that knew were the survivors, and not even their families. I didn’t even tell my wife about this or my kids. They knew I lost a ship and they knew I got the Bronze Star medal.

I belonged to the VFW in North Bergen. I used to go religiously, never missed a meeting. One night I was eating supper, and I said to my wife, “You know, I don’t feel like going to the meeting tonight, I think I’ll just stay home and watch TV.” So I get up from the table, come into the living room, and open the paper. I’m looking down the schedule, and I didn’t usually stay up till 10 and the “20/20” show came on at 10, so I look all the way down, and it says “20/20. The mystery surrounding the killing of 750 GIs in a D-Day rehearsal.” And when I saw it, I couldn’t believe it. Forty years now, Holy Christ, don’t tell me that this is about Tiger, I don’t believe it.

So then I got ready to watch it at 10 o’clock. I sit in the chair, put it on, and sonofabitch, they show you the ass end of the third ship, the third ship that got hit, they blew the back end of it, that’s the 289. When I saw that, I said, “Oh my God, it is!” How the hell did this happen? Who’s doing this now? I watched the whole thing. I was amazed. I was dumbfounded.

In the beginning, when they took us off the ship to a hospital after this thing happened, we were all told that we should never talk about this to anybody. Even the guys in the Army, I met this guy who lives in Forked River, he was on the lead ship, the 515, and he said that as soon as this thing started popping, they had all the soldiers go down below decks. They didn’t want them to see anything or understand what’s going on. And the next morning their commanding officer told them, “Nothing happened last night. Remember. Nothing happened.” It’s all documented.

I watched the show, and that particular night my nephew happened to be twisting the dial, he came across it and he said, “Isn’t this what happened to Uncle Angelo?” So my brother watched the whole show. And the next morning, he calls the studio and talks to the producer, a woman, her name was Nola Saffro, and he says to her, “I watched your show last night on Tiger, and my brother’s a survivor of that.”

So she flipped. She says, “Where is he? Where does he live?”

He says, “Right across the river.”

She says, “Please, give me his phone number.” And the next night, at 5 o’clock, I was eating supper and the phone rang, and it was her. She spoke to me for an hour. She wanted to know everything that happened.

And at the end of the conversation, she said to me, “I have the names and addresses of a lot of your shipmates. They’re scattered all over the country, there’s one guy in England, who stayed in England and married an English girl. I have the name and address of John Doyle,” who was the skipper who came back to save us, he lives in Missoula, Montana.

I said, “Please, give me it.” And then she had the name and address of Dr. Greene. Dr. Greene was one of the doctors, he was a captain, in the Army field hospital where we were brought the following morning. I didn’t know him then. I didn’t even know he was there.

What had happened was the head doctor in this hospital got all the doctors together before we got there, and he said, “You’re going to get a load of casualties this morning. You don’t take any names. You don’t ask any questions. You don’t keep any records. Just treat them as they are. Anybody that gets caught talking about this will be court-martialed.” He’s telling this to guys like captains and all.

Dr. Greene lives in Chicago, he’s a pathologist. Ralph Greene. I met him and his wife, Sylvia, in New York. So after the war he goes home, back to his practice, and he was telling me, every once in a while he used to think about the thing and wonder where the hell did all these guys come from, and why did they threaten us with a court martial? Because nobody knew.

So in 1974, the government passes the Freedom of Information Act. As soon as he saw that, that was it. He went to Washington, went into the archives, he wanted to see the box on Tiger. There still were certain things that were classified, but they gave it to him. When he opened that up, he told me when he started reading it, he couldn’t believe it. And he says, How the hell did they keep this thing so quiet, a disaster like this? You know what I found out yesterday at the memorial in New Bedford? This guy, by putting figures together, I knew the figure was low. He said there were over a thousand guys killed. See, they came up with this figure of seven hundred and something, that’s bullshit.

So he sees this stuff and he gets crazy. He decides that he’s gonna investigate the whole thing through. So he spent months traveling all over the country, finding guys, locating survivors, and what he does is when he gets enough good information together, he goes to the 20/20 show. So they looked at it, they loved it. On the 20/20 show they interviewed John Doyle, the captain. Dr. Greene. Manny Rubin is the fellow who stayed in England, married the English girl. He just died recently.

When she gave me all these names and addresses, I figured the first letter that I want to write is to Dr. Greene. I was so thankful that he went to the trouble to do this. So I write him a letter, and I explain who I was, what ship I was on. What happened. A brief synopsis. And he sends me back a letter a week later, he says, “Please, do me a favor. Put down on paper everything you remember from the time you left Brixham until the time you ended up in the hospital. Everything.” I put together a six-page letter. He said the reason he wanted to do all this was that he’s thinking about writing a book. He was going to call his book “Tiger Burning.” Which was an appropriate title, too.

Then I wrote to Captain Doyle and I thanked him, because if he wouldn’t have come back I wouldn’t be here today.

In the letter to Greene, I explained that I couldn’t feel my legs, and I was worried about gangrene, and that they were going to have to amputate my legs. Now Greene takes this letter, he makes copies of it and he sends it out to a few guys.

Now it’s four and a half hours I was in the water, and I’d just about had it. I figured I wasn’t gonna make it. And all of a sudden, I’m looking in the distance, it’s still dark. I see this light going up and down, and it seems to be getting bigger. So when I see this, I immediately assume that help is coming. And when I did that, I passed out. I figured, I saw help’s coming, I couldn’t hang on any more, I just passed out.

What happened, after the third ship got hit, the commander of the convoy told all the remaining LSTs to get the hell out of there, and go back to England. So they took off, five LSTs, and an LST only goes, top speed, loaded, five knots. So they take off, and they’re heading back to England, and they’re under way for quite a while. In the meantime, this Captain Doyle, on the 515, he says to the commander, “I’m gonna turn this ship around, I’m going back. There’s got to be a lot of guys in that water alive yet.”

The commander said, “If you turn this ship around I’ll have you court-martialed.” Now this guy’s a commander, and Doyle was a lieutenant JG. Doyle said to him, “This is my ship and I’m going back.” He wasn’t concerned about the Navy crew, but he had all these Army guys. He made an announcement over the PA system, he said, “I’m going back. Would you rather stay or go back and fight?” So they all yelled, “Let’s go back and fight!” So now he starts back, what, like I said, five knots.

But see, the reason the commander said “I’ll have you court-martialed,” this is normal procedure in the service, you can’t jeopardize a ship loaded with guys to go back and pick up guys. But Doyle knew that when he got back to that area, it would be dawn, and once it gets dawn, E-boats don’t hang around, they like it at night, sneaky, hit and run. And he was right. So when they came back, they lowered two boats to look for survivors.

When I wrote the letter to John Doyle, he wasn’t feeling well so he couldn’t answer it, so he called up this guy Floyd Hicks, who lives in California, who was on his ship, and told Hicks to call me up from California and to tell me that he got my letter, and that he was glad to hear from me, and that he wasn’t feeling well. So one Sunday night I get a phone call, and I didn’t know this guy from Adam, Hicks in California. So he said, “I was on the 515 with Doyle,” and an engine room guy, too. And he said, “Doyle asked me to call you up because he isn’t feeling well.” In the meantime, he says to me, “I have the phone number of a guy named Joe McCann.”

I didn’t know who he was. But Hicks told me that McCann was one of the guys who lowered his boat and went around looking for survivors. So I wrote Joe McCann a letter and I told him about Hicks and Doyle, and I told him who I was, and I said, “I know that there were two boats lowered that went around looking for survivors,” so I said, “The odds are fifty-fifty that you are the one who picked me up.”

About three or four days later on a Sunday night again, the phone rings, it’s Joe McCann. And I told him on the phone, “You know, Joe, I wrote to tell you that being that you were one of the coxswains that picked up bodies, the odds are fifty-fifty you picked me up.”

He said, “I did pick you up.”

I said, “How did you know it was me?”

He said, “The reason I knew it was you is that you were unconscious, but you were mumbling about your legs.”

He told me that when the captain told him that they were gonna lower the boats and go around looking for bodies it was still dark, he immediately ran into his locker and he got a Navy lantern. So he took the lantern and he hooked it onto the bow because he said he didn’t want to go through the water and kill somebody that was alive. So he was just drifting slow and looking. And this is the light I saw. And he said, “The first run that I made in the area of your raft, we thought you were dead, and we passed you right up.” Then he said that on the way back he passed us again, and the guy in the boat with him said, “You know, I think I saw one of them guys moving.” And sonofabitch, I mean, how close can you come not to, after all I went through. I mean, I cried. When I hung up I cried.

Now this is a comical part of the story. When I woke up in the hospital, my executive officer was one of the few officers that survived, James Murdoch, he was a professional baseball pitcher for one of these Southern teams. Lefthanded. He was really good. He used to walk around the deck a lot of the time with a glove and a ball, bouncing it, and he was a rebel. He was from Virginia. Nice guy. I’ve got a picture of him. And he smoked cigars. But good cigars. He used to buy them in a box. So I wake up, and after a while I see him, he’s standing there in his underwear, and you know what he said? I’ll never get over it, I couldn’t believe what he said. “Sonofabitch,” he said. “I had six good boxes of cigars on that ship.”

And I said, “You sonofabitch, you’re worried about your cigars, all these guys got killed.” I couldn’t believe it.

After they checked me out and treated me, they said there wouldn’t be any permanent damage to my legs, and told me not to be concerned. Then they took the survivors and split them up in small groups. And they put us in, they called them rest camps, but I called them isolation camps. Because we weren’t even allowed passes or to talk to anybody.

Now this is the payoff. We go to this rest camp, and we all know that the rule in the Navy is this: If you lose your ship, you have to go back to the States for 30 days survivor leave because you have to get all your gear back again. We lost everything. When I got there, they gave me Army fatigues, a towel, toothbrush, a piece of soap. That’s it. And we all knew that you have to get survivors’ leave. So after we’re there three weeks, this same guy, Murdoch, he was the executive officer, he comes out one morning and lines us all up, and he’s got papers. I said to the guy next to me, “This is it. We’re going back to the States.” So he starts reading names off, he says, “You guys are all petty officers, and all experienced, all went to Navy schools, and you’re all going to be reassigned to LSTs to make the invasion of Normandy.”

I could feel my blood getting cold. They’ve gotta be kidding. I said, “What the hell are they trying to do, kill us? Chrissakes, it’s only three weeks ago we were out there, and now we’re gonna go back? I couldn’t believe it.

——-

(Angelo Crapanzano was aboard an LST that carried troops and tanks ashore at Utah Beach on D-Day. He took part in a total of 23 missions. For more of Angelo’s story, read “A Mile in Their Shoes”)