The Island of White Witches

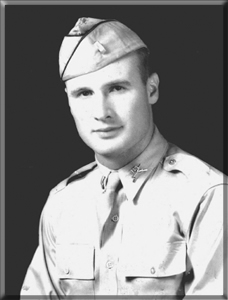

Col. Charles B. Bryan

At the 1995 reunion of the 90th Infantry Division, Col. Charles Bryan gave me a copy of a manuscript he had written. At the time, he had only made ten copies, for his grandchildren. I have always treasured my copy, as it is one of the best books I have read about World War II. When I called in 1998 to ask his permission to use this story, he said he had 50 copies of the book made up a couple of years back, and when those were all gone he had 50 more made. He is down to his last two, and is thinking of making another 50.

Col. Bryan joined the 90th as a replacement officer in Normandy in July of 1944.

©1998, Charles B. Bryan Sr.

I was assigned to the 90th Infantry Division on the 14th of July. The first person I met was Lt. Smith from the 176th Infantry days. He shared with us his experiences as a rifle platoon leader, and temporary company commander. He was picked to orient us, because he had done so well. I never did see him again or learn what happened to him. The next day I went to the 358th Infantry Regiment. Lt. Donahue welcomed us with a brief history of the Regiment.

I was assigned to the 3rd Battalion and put in command of “L” Company. The 3rd Battalion had been put in reserve in the vicinity of La Valaisserie after taking Hill 122 in the Foret de Mont Castre. The Battalion only had four officers and 126 enlisted men left in the three rifle companies, but L Company had no officers and only 27 enlisted men. Staff Sgt. Burk was acting C.O. All of these men had dark circles around their bloodshot eyes. Their skin had a sallow look and they moved around like zombies. Replacements came in until we had six officers and 170 men. We organized the company, making all the old men sergeants. They all worked out well except one.

Our first assignment was a defensive position on the Seves River in front of the Island. The French called it the Island of White Witches. This was a very good way to be introduced to combat.

We relieved the 1st Battalion after dark and suffered our first casualties before daylight. Lt. Ringler received a direct hit on his foxhole. When someone was wounded the stretcher bearers would stop by the company C.P. on their way to the aid station. 1st Sgt. Burk would always kneel down and talk to the wounded in a very compassionate way. It was a long time before I learned that Sgt. Burk was asking where his foxhole was located so he could go there to get his coffee and cigarettes out of his remaining rations.

I remember the odors in this area. The rich black earth had a very distinctive odor and we were very close to it in our foxholes. All the farms had large wooden barrels of cider in their barns, and most had been pierced by artillery shells. The cider, mixed with the rich earth, gave off a very strong odor. Around the Company Command Post we collected the equipment of the wounded, and it was covered with dried blood. The dead cows were very prevalent. The odor of death, both human and animal, was everywhere.

On the left boundary of our area there was a wagon road (two deep narrow ruts) through the fields and going through the hedgerow on across the marsh to the river. A major from the division or corps headquarters walked down this road and went through the hedgerow (that was our front line) into no man’s land. The men who saw him jumped into their foxholes expecting some type of fire from the enemy. A machine gun fired several bursts at him, but luckily he was not hit. He ran back through the hedgerow, white as a sheet and mad as hell. He asked why no one had told him about the machine gun.

The sergeant answered that, “You didn’t ask anyone, Sir.”

When he was leaving on shaky legs, a private piped up, “Thank you for locating that machine gun. We’ve been trying to find it all morning, Sir.” He should have checked in the Company C.P. before coming into the company area.

During this period we were shelled by the Germans whenever a target presented itself, or a tank or truck came into our area. Several times someone back at Division would decide that we needed the tanks on the front line with us. When the tanks arrived one always managed to run over the telephone lines laid on the ground. It would not only cut the line but would wind up half a mile of wire around its tracks. When the Germans heard the tanks, they would shoot at them with 88s, artillery and mortars. We usually had several casualties before we were able to order them out of the area.

We had several casualties from tree bursts. That’s when the artillery shell hits a tree and explodes. The fragments not only go up and out 360 degrees, but in a downward direction. Men were hit while laying down in their foxholes. We had to put tops on the foxholes if they were near a tree. The problem was to find material for the tops. We used limbs, boards and sheet metal, then covered it with six inches of dirt. Sgt. Cox and I were working on our hole. I remembered seeing some boards in a field on my last trip to Battalion Headquarters. When we went through the opening in the hedgerow to the field, Sgt. Cox dove for cover on the ground. I followed suit without any questions. An 88 shell passed where we had been moments before.

The Germans expended three shells on us. As each exploded we hugged the ground harder and flattened out more. Usually the Germans didn’t use more than one shell on such a small target, but we didn’t feel flattered by three shells. We used a different route back to our foxhole.

I asked Sgt. Cox how he knew to hit the ground. An 88 shell travels faster than sound, so he couldn’t have heard the cannon shoot. He couldn’t explain it, but something told him to hit the ground. This happened several times during the War and it saved both of our lives.

Sgt. Cox had to go to the hospital to have a cyst removed. It was caused by the big radio that he carried on his back. Several radios were hit while on his back. When he returned in January, he stayed at Battalion Headquarters as a switchboard operator.

Someone with good intentions would decide that the front lines should have hot chow. The kitchens would move up as close as possible, and we would send back a few men at a time for hot chow. The Germans always spotted the movements and shelled us. The tanks and hot food were forced on us several times before we convinced Division that we were better off without them.

The Regiment attacked the Island on the 25th. The 1st and 2nd Battalions attacked through the 3rd. They laid down a good artillery barrage, but the troops were so slow in moving off that they halted the attack. On the second attempt they didn’t do much better. Both Americans and Germans suffered heavy casualties when they crossed the marsh and river. Chaplains Stohler and Esser arranged a three-hour truce with the Germans for evacuation of wounded. The American and German medics and litter bearers almost bumped into each other as they worked. During the night the Germans brought up reinforcements, counterattacked and captured the force on the Island. The 357th and 359th Regiments attacked the next day to encircle the Island, but the Germans pulled out before the trap was closed. This was the last battle for the 358th in the Normandy hedgerow country. I had a ringside seat and learned a lot from the mistakes of the 1st and 2nd Battalions.