Courage Under Fire (excerpt)

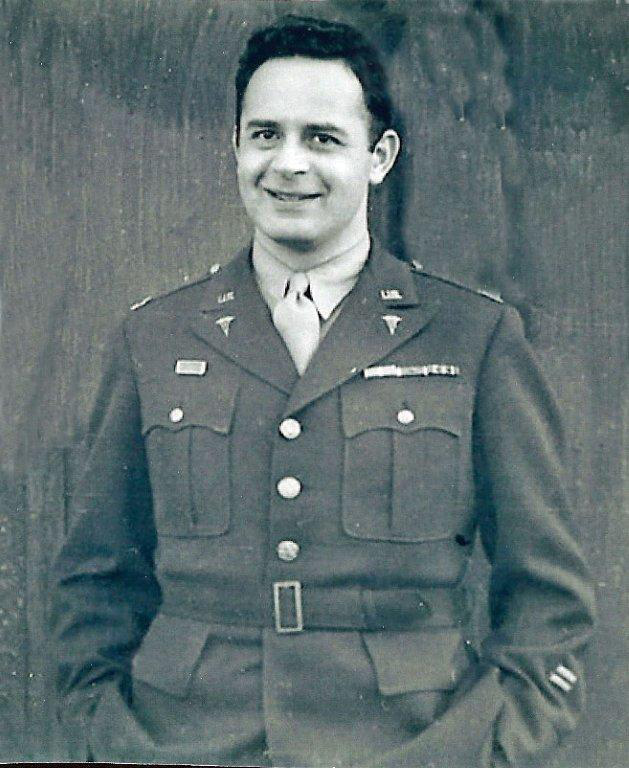

Aaron Elson: Now was this in the newspaper? “Captain De Scherer wins Bronze Star under fire.” I’ll just read this. “Englewood dentist steps into job of surgeon in stress of battle. … Captain Morton P. De Scherer of Englewood has been awarded the Bronze Star medal for meritorious service. …

“[His] citation reads, ‘Captain De Scherer, as a dental officer, assumed the duties of assistant surgeon of the 3rd Battalion of the 8th Infantry. Displaying great courage, skill and devotion to duty he personally rendered and directed expert medical care at the battalion first aid station until he was relieved by a surgeon.

“‘Frequently under heavy enemy fire, he performed his duties in an outstanding manner, often going without sleep or rest for long periods. His courage, medical skill, and complete disregard for his own safety saved innumerable lives and reflects great credit upon himself and the military service. Captain De Scherer, who has been overseas for the past year, participated in the D-Day invasion and holds the Purple Heart and the Presidential Unit Citation.’”

Morton De Scherer: There’s [a picture of] Teddy Roosevelt [Jr.]. He was our assistant division commander for the 4th Division. He died when we were [at Ste. Mere Eglise].

I met him, Teddy Roosevelt. One day we were stationed at a camp in Honiton, England. It’s down in Devon, right on the shore, and we went through maneuvers. We had a big division parade and we were addressed by General Eisenhower, General Bradley, Teddy Roosevelt, and the Air Force … They all talked to us, and when they were there we knew we were it. Because when those big brass come, we knew we had a big job ahead of us. We didn’t know what it was, but we knew. And then, after some more training we went to this marshaling area, where everybody was getting ready for D-Day. And while I was getting ready at the marshaling area, I was bathing, and an officer came in, and told me that I just had a baby boy. So a few days before D-Day, May 12, is when we had the baby boy. Who’s right here now, he’s working with me.

Aaron Elson: What went through your mind, becoming a father and being in a position like that?

Morton De Scherer: I was elated and also awful sad, and I think the biggest thing that went through my mind is I’ve got to get through this. That was in my mind the whole time I was there. Eventually I got pictures of him.

Aaron Elson: Do you remember what Teddy Roosevelt said?

Morton De Scherer: No, they were all pep talks. We were left with the impression that many of us weren’t going to come back. They were pretty blunt about that.

Aaron Elson: How did you cross the Channel, in what kind of a boat?

Morton De Scherer: It was a landing craft, an LST.

Aaron Elson: Were you in the hold, or did you ride on top?

Morton De Scherer: The night before D-Day was very rainy. There was no shelter. There was a two and a half ton truck with a canvas top on it, and I sort of made a hammock out of it and slept on it. It felt like I had a pretty awesome responsibility because, in the first place, I was the only medical officer on ship, and Colonel Van Fleet, who was our regimental commander, was on board, too.

So we slept through a drizzle. And then of course we took off in the morning and it was quite an amazing, the preparation, logistics were just amazing. It was just one of the most wonderful things. I’m sure it would have gone better now with better communications, but it was amazing.

Aaron Elson: What was the sight like? When did you see the vast group of ships?

Morton De Scherer: We were being escorted by larger ships, and there were many smaller ships in some sort of formation going across the Channel. And I’m sure there were submarine covers, because there were a lot of German boats. The Germans wouldn’t even let us practice in the Channel once.

Aaron Elson: I heard about that. Were you with them?

Morton De Scherer: I was on detached service with the Navy, and we had a joint operation.

Aaron Elson: Was that when they had these E-boats?

Morton De Scherer: Yes.

Aaron Elson: Tell me about that.

Morton De Scherer: E-boats would come across at night, and they’d hide near the English shore. And then they’d just take off, go right through a bunch of boats, and whatever was in their way they’d would shoot, with torpedoes. And they’d make their way for the French shore. We had casualties.

Aaron Elson: You being a medic, did you have to deal with the casualties back then?

Morton De Scherer: There were no casualties on our boat. I don’t guess it was too eventful. We had two reporters, one reporter who’s still alive, Larry LeSueur was on our boat. I saw him on TV awhile ago, and another photographer, Robert Landry. I got to know them.

When we got close to the French shore, Colonel Van Fleet left our boat, got into a smaller boat with a small contingent of men, about 20. One of those men was a radio operator, his name was Blum. I remember him very well because I couldn’t understand how that fellow with all that equipment on his back was ever going to make it. I always wondered if he did or not.

Van Fleet [later General James Van Fleet] was born up here in Coytesville. There used to be a town Coytesville. He died about two or three months ago, he was a hundred years old. He used to tell me Coytesville, New Jersey, that was a town. I don’t think the town is chartered anymore, but it was just inside Fort Lee.

Aaron Elson: Which beach did you land on?

Morton De Scherer: I landed pretty early on Utah Beach. I remember a few outstanding things. I remember one lieutenant whose name was Mills wanted to get a bird’s-eye view of the whole thing so he sat up high in the boat. I remember the name Mills because his father was the dental surgeon general of the Army, and he got popped off.

Aaron Elson: By a sniper?

Morton De Scherer: Yes.

I guess somebody saw him sitting there while we were coming in. But we landed, and I didn’t have to tread too much water. I remember the fire, and I remember crawling. I remember every little grain of sand. And I remember passing a guy, I thought he was crawling too but he wasn’t, he was dead. And I didn’t know where anybody was from my outfit, because they came in on different boats. So I saw a Naval aid station, and they put me to work right away. In a few minutes I saw some of my own officers and men come back. They were wounded already. I treated some of them. I remember one was a Lieutenant Sconyers. I don’t know why I remember his name but I remember him.

He wasn’t wounded too badly because he was walking. And he was already taken care of by an aid man. So it was a matter of getting him back on a boat. But at the Naval aid station we treated quite a few soldiers. And I remember seeing, well, while I was still on the boat, the Navy was there and they were firing round after round, and I think if it wasn’t for them we never would have made it. And the Air Corps helped us.

You had the feeling like those battleships were firing so fast the battleship was listing over. An amazing sight.

Aaron Elson: What were most of the wounds from? What were the Germans firing?

Morton De Scherer: Eighty-eights and machine guns. We had to cross a small stream. There was a bridge there, and they had that zeroed in. This was just coming off the beach going back toward Ste. Mere Eglise. And we had to cross the bridge one by one. When a sniper shot, one of us went across, before he would get a chance to shoot again. And then I remember seeing another GI, he was on one knee, holding his gun, and he was rigid. He was dead. He was just like a statue. And there’s nothing you could do for him, but there were others. Mostly all we could do was pick the men up. If they had fractured limbs we’d splint them. We’d try to stop hemorrhaging and give them plasma when we could. Bandage. Morphine. We carried a bunch of morphine with us, little syrettes.

Aaron Elson: At this point I guess there was no need for your dental skills.

Morton De Scherer: No dentistry done until we got to a rest area when we took out our equipment. And now you had to be careful because a lot of it was shiny and that’s all the Germans need.

Aaron Elson: You said you went in early in the morning of June 6th?

Morton De Scherer: Maybe in the second or third wave. We were preceded by the paratroops. In that marshaling area, just before D-Day, almost every hour we were given photographs of where we were going. We knew how deep the hedgerows were and how long the fields were. We knew so much it was really amazing. But those hedgerows and those fields weren’t big enough to accommodate the gliders. A lot of them cracked up, and you’d go into one of those gliders and you’d see a bunch of, well, most of them were dead, and they were just like splintered, bone splinters. They’d land there and they’d smash into the hedgerows. They were made of stone. The gliders, they had a hard time; they had no power. I remember they used to throw big bundles from the air, with medical supplies.

Aaron Elson: Did supplies run low at any point?

Morton De Scherer: Yes, they did. Of course, we could only carry so much on our backs, and the gliders would provide more supplies.

Aaron Elson: So even after the invasion they sent gliders in?

Morton De Scherer: Yes, for a few days.

Aaron Elson: How far inland were you when you first set up a medical station? Did you get into Ste. Mere Eglise?

Morton De Scherer: It was after Ste. Mere Eglise. We had dead German soldiers too, and I took this map off of one of them.

On the beach, they had two cages there, one for officers and one for GI men. And I remember seeing this one German officer strutting. He wouldn’t sit, he’d just go back and forth and back and forth, and finally some of his own, I guess some of the shrapnel from the Germans shot him. And when you captured one of those German officers and you wanted to treat him, you had to get their boots off. They wouldn’t let us take their boots off.

I started to do this, but I got too busy. We landed here [Ste. Mere Eglise] and then we went here in Montbourg, and there was a church with a big steeple and the Germans were in that steeple and the Navy knocked it out. They chopped it right off. And then we went up to Cherbourg and our outfit took Cherbourg. That was the 28th or 29th. In Cherbourg the Germans had an underground palace, almost like a palace I would describe it. It had little railroad tracks and cars, and they had amazing stashes of whiskey, liqueur, cigars, coffee, it was unbelievable.

Aaron Elson: That was where they had the submarine pens?

Morton De Scherer: Yes. That’s where Admiral Doenitz was. But they really must have had some life. And then we started going back. Then we went to Perier, and then St. Lo. General McNair was killed on July 25th I think, before we took St. Lo. There were so many airplanes in the sky that you couldn’t see the sky. And the earth was rumbling like an earthquake. It was dark. It was in the middle of the day but there were so many airplanes it got dark. And you could see that the Germans shot some of them, and the pilots were bailing out. While they were bailing out, coming to the ground, the Germans would shoot them. You could see the pilot double up right in the middle, off his parachute.

Aaron Elson: When the bombs killed General McNair, how close to that were you?

Morton De Scherer: I was right there, because I ran like crazy. And the fellow in back of me said I was as good as a tank because I ran right through one of those stone hedgerows. I mean, I just really took off. And there were a lot of people there that were near where General McNair got killed. Ernie Pyle was there. Ernest Hemingway was there. That was quite a thing, that breakthrough.

Aaron Elson: What was your reaction?

Morton De Scherer: I was real upset at the time. There was an awful lot of cursing among the GIs. And there were casualties. Then we got to a stage where there was a pretty fluid front line. There wasn’t any front line, and that’s where I got stuck with this aid station. And the worst part of the job really, you had casualties to attend to and to fix them and try to put them together, but the worst part was to figure out which one to treat. Because we only had two or three jeeps that were converted to litter bearers, and we had a very narrow corridor where we could let them go. So all the soldiers couldn’t be evacuated, and it was up to me to figure out which ones – some stayed back and died – couldn’t be treated. I didn’t like that job. I remember seeing those fellows, if they were hit in the stomach or had internal bleeding, you said, well, this guy hasn’t got a chance to make it, whereas another guy who had fractured limbs or if you got the bleeding stopped he would make it. There’s another fellow sitting there, I’ll never forget this, he was shot in the head, and the cranium, you could just pick it up and move it and see his brain tissue, and he was sitting there smoking a cigarette. See, if we could evacuate them, but some of them you couldn’t get out. Being the aid men, we had a hard time figuring out which ones.

Aaron Elson: That fellow, was he evacuated?

Morton De Scherer: He was evacuated. You never know if he ever made it. Well, the prognosis can’t be good because some infection has to set in. And we had penicillin, but it was pretty new then, so we didn’t have that much.

Aaron Elson: How were you wounded?

Morton De Scherer: German tanks came into our area. That was on the 29th of July. We had just gotten through St. Lo, to a little town called Notre Dame de Semilly.

Aaron Elson: What were the circumstances surrounding that?

Morton De Scherer: It was just a time when there was no front line, and all of a sudden they’d be there. I guess when you’re in war it’s not very organized sometimes. And I’m not a trained military officer.

Aaron Elson: Was it in the morning, or the afternoon, or night?

Morton De Scherer: It was daytime. I don’t remember what time of day.

Aaron Elson: Did you have to pack up the aid station every day? How long had it been set up?

Morton De Scherer: Sometimes you don’t even have an aid station. I might have a half a dozen aid men with me, set up a little place. Sometimes you look for a house where there’s a basement, so you have a little shelter. You try to find a place where there’s some shelter, a few men get together and you really work out of your kits, mostly.

When you go into a tank after it’s been hit, especially if it’s right after it’s been hit, you’re looking at soldiers that are sitting there and they’re almost like stew.

Aaron Elson: Did you ever have to do that?

Morton De Scherer: To go into a tank? Yes. Just like, just like coming to a can of C-rations, something like that. It was all enclosed. They didn’t have much room in there. If they got a direct hit … so it was a pretty terrible sight.

Aaron Elson: Some of the tankers have described the smell.

Morton De Scherer: The smell of war was unbelievable, the smell of death. That’s something you can’t forget either. The only time you can catch it is if you go through a cancer ward in a hospital sometime, where tissue is dying, you might get a whiff of it. But this is real concentrated smell, and it’s not only the men that were dying. The men were cleaned up pretty well, but all the animals in the field, the cows, they’d get hit and they’d swell up, and smell something awful, all over the country.

Aaron Elson: Can you compare it to something, like you just compared it to walking through a cancer ward?

Morton De Scherer: That’s the only time, I walked through the hospital here once and I smelled it and it brought it back to me. Just a small whiff. Dying tissue. Like I’m sure when the police go into one of these places that has a dead body for several days.

Aaron Elson: How would you treat burn patients?

Morton De Scherer: I didn’t see too many burns. I don’t think I treated any of them. I saw mostly shrapnel injuries, and a lot of fellows broke down, like became psychotic.

Aaron Elson: How would that manifest itself?

Morton De Scherer: They would get very depressed, or … I can recall one young fellow just raving mad, and frothing, real froth like beer coming out of his mouth. Sometimes you’d see that.

Aaron Elson: And how would you treat someone like that?

Morton De Scherer: We just would give them a sedative and send them back. You had to send them back. I don’t remember what we used.

Aaron Elson: Let’s go back to July 29th, when you were wounded. When did you first see the tanks coming in?

Morton De Scherer: I don’t think I saw it. I think all of a sudden it was there. I was probably busy treating somebody. I wasn’t the only one hit, there were quite a few that were. The aid men that were there, they treated me, tried to stop my bleeding, and they got me on an ambulance. And one of the aid men came with me, I think his name was Windsor, and got me to one of those field hospitals. And I remember seeing a surgeon there and pleading with him to keep, I had been hit in the arm, so I didn’t want to lose my arm. I told him I was a dentist and I needed it, but I don’t know if that meant anything. He treated me wonderful, and they put a great big cast all over me, a chest cast and everything. I stayed in some evacuation hospital, and after a while they flew me to England.